Principal’s Post on Empowering Young Women

Since 1935, Our Lady of Mercy Catholic College has held a legacy of instilling the values of leadership, excellence and service, nurturing confident young women. We empower our girls to make their make on society with confidence and compassion.

Dear Parents / Carers,

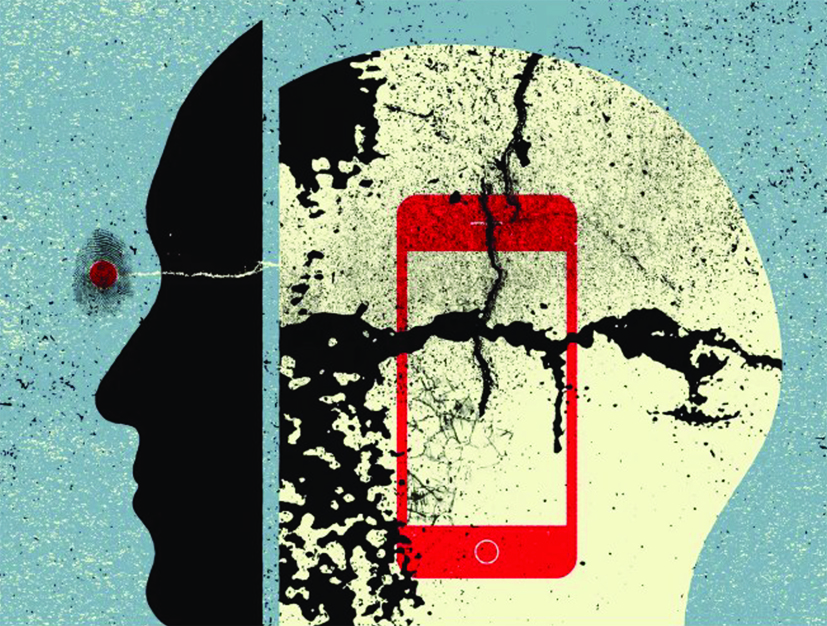

The following article, published in The Learning Dispatch by Carl Hendrick on July 26, 2025, presents compelling evidence linking smartphone usage to a decline in mental health and overall wellbeing.

| Recent global research has highlighted a strong link between early smartphone use and poorer mental health outcomes in young people. Students who received smartphones before age 13 were found to have higher rates of anxiety, depression, and emotional challenges in their late teens and early twenties. While the evidence is largely correlational (not definitively causal), experts argue that the consistent patterns across cultures and studies are too significant to ignore. Factors such as unsupervised social media use, disrupted sleep, cyberbullying, and reduced family interaction all contribute to these outcomes. Importantly, the concern isn’t about phones themselves, but about early access to social media platforms designed to capture attention and provoke strong emotions. These environments can be especially harmful to children who are still developing emotional regulation and self esteem. As a school community, we encourage ongoing conversations about healthy technology use and support parents in making informed decisions about when and how their children engage with digital devices. |

Banning Phones: How Much Evidence Do We Need?

Evidence shows early access to smartphones is strongly associated with poorer mental health and wellbeing. But a lot of the evidence is correlational. What does that mean for schools and parents?

What’s the effect of giving kids smartphones before 13? Not Good. A new global study, covering data from more than 100,000 young adults, reports that those who first received a smartphone before the age of 13 show markedly poorer mental health outcomes in their late teens and early twenties. The most striking associations are with increased rates of suicidal ideation and diminished emotional regulation. The authors claim these findings hold across a wide range of countries and cultures. Strikingly, they are not an artefact of one region or demographic.

What is driving these effects? The study highlights several mediating factors: early and unsupervised exposure to social media platforms, greater vulnerability to cyberbullying, chronically disrupted sleep patterns, and a weakening of family relationships through reduced direct interaction. These factors, taken together, create a developmental environment that undermines resilience and mental health at a crucial stage. This new study is typical of many but is the evidence causal?

Importantly, the study does not claim definitive causation. In the language of research, the evidence is correlational, not causal. In other words, we cannot yet say that handing a ten year old a smartphone will cause poor mental health. But we can say that, on a population level, early smartphone ownership is consistently linked to poorer outcomes. The question is how strong is that link? And should we be recommending sweeping policy based on a link?

This distinction matters, and sceptics often use it to argue against policy action. However, to my mind, the authors of the study make an unusual and powerful argument: even in the absence of causal proof, the sheer scale of the associations, combined with the plausible mechanisms of harm, justify immediate precautionary steps.

This kind of thinking is not new. Seat‑belt laws were introduced well before randomised trials could prove beyond all doubt that they save lives. Lead was removed from petrol not because of a single definitive study, but because of converging evidence from toxicology, public health, and developmental psychology showing serious risks.

Beyond Correlation: Multiple Lines of Converging Evidence

Researchers are right to be cautious about correlational data but as Jean M. Twenge has pointed out, there is compelling, converging evidence from multiple data sources pointing in the same direction. Her analysis of Monitoring the Future data shows that between 2012 and 2019 (when smartphones and social media moved from optional to almost universal among teens) depression among girls rose by 74% (13 percentage points) and among boys by 56% (8 points).

The spike during the pandemic years was significant but smaller, and by 2023 those pandemic‑related increases had receded, yet depression rates remained far higher than in 2012. In other words, even as the immediate shock of COVID‑19 faded, the long‑term upward trend in teen depression tied to a screen‑based social life continued. This pattern, where the rise predates and outstrips pandemic effects, adds weight to the argument that technology and social media use are not just correlated with but are plausibly driving much of the current mental health crisis among adolescents.

Furthermore, as Jonathan Haidt has pointed out, there is compelling, converging evidence that goes well beyond simple correlation.

Longitudinal studies now show that heavier social media use predicts later increases in depression and anxiety, not just the other way around. Randomised experiments find that reducing social media use leads to measurable improvements in mood, and natural experiments (such as the roll out of Facebook or high‑speed internet) show community‑wide rises in mental health problems once access expands, particularly among girls. Combined with clear dose–response patterns and effect sizes comparable to established public‑health risks, these findings make it increasingly difficult to dismiss social media’s role as anything less than a significant causal factor in the current adolescent mental‑health crisis.

Perhaps most compelling are the “quasi-experiments” that examine what happened when social media arrived in different communities at different times. Braghieri, Levy, & Makarin (2022) studied Facebook’s original rollout to specific colleges and found that “the roll-out of Facebook at a college increased symptoms of poor mental health, especially depression.” Studies of high-speed internet rollout show similar patterns: in Spain, Arenas-Arroyo et al. (2022) found “a positive and significant impact on girls but not on boys” when high-speed internet arrived, with effects on sleep, homework time, and family relationships. In British Columbia, Guo found that high-speed wireless internet “significantly increased teen girls’ mental health diagnoses (by 90% ) relative to teen boys.”

What We’re Really Debating: It’s Not The Phones

It is worth underlining what this debate is really about. It is not about banning all phones or denying children any access to technology. A phone can be useful. For example, texting a parent after school, using a maths app, looking up a bus timetable. The issue is not the hardware. The issue is the gateway it opens into billion dollar, algorithmically‑curated, AI driven social media environments long before a child’s sense of self, identity, and emotional stability are formed.

Platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat are not neutral spaces. They are engineered to maximise engagement through what is called adversarial design: systems that exploit cognitive vulnerabilities rather than serve human intentions. These platforms thrive by feeding users content that provokes strong emotions such as outrage, shame, envy, and fascination because these emotions keep us scrolling. Even adults, with decades of life experience, struggle to resist these hooks. For children, the effects can be far more destabilising.

Consider what this means for a ten year old who is still developing the neurological foundations of self control. Sleep is easily disrupted by late night scrolling; social comparison begins to warp self esteem; algorithmic feeds expose them to communities and content far beyond their emotional maturity. A 2023 report by the US Surgeon General highlighted the links between heavy social media use and increased anxiety and depression among adolescents.

Some food for thought……